My journey to hosting Goin’ Down South on WXNA started when I was a Capitol Hill reporter, way back in 2001. Washington, D.C., was a stressful place back then. The 9/11 terrorists had crashed an airplane into the Pentagon, and envelopes containing anthrax started showing up in congressional offices. I’d been near one of these offices when one of these envelopes showed up and I couldn’t get a straight answer as to whether there was any chance I had been exposed to anthrax, bacterial spores that can kill you if you inhale them.

I decided it was time to get the hell out of Dodge. So I took a road trip — not just any road trip, but a Southern music pilgrimage. I’d been to the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival a dozen times, but despite growing up in Tennessee, I’d never been to Memphis. I’d never been to the Mississippi Delta, despite my love for the blues. And I’d never been to Duane Allman’s grave. It was time to visit all those places.

So I drove south on Interstate 81, stopping first at the Carter Family Fold in rural Hiltons, Virginia, where Janette Carter was waiting for me on the porch of her father’s store. Janette was the daughter of A.P. Carter and Sara Carter, who teamed up with Maybelle Carter to go over the mountain to Bristol in 1927 to record some tunes for Ralph Peer — part of the Bristol sessions that made the Carter Family and Jimmie Rodgers the first big stars of country music. Janette, who was keeping the Carter Family tradition alive by hosting weekly concerts, explained to me the difference between old-time and bluegrass music — bluegrass is simply old-time “all sped up,” she said. Somewhere I have a tape of our conversation. Maybe I’ll dig it up and play excerpts on Goin’ Down South sometime.

Then I drove into Bristol, to hear a weekly bluegrass concert at the Bristol Mall, an event held by the Birthplace of Country Music Museum, which at that point was housed in a vacant space in the mall. Now the museum is housed in a grand old brick building in downtown Bristol, which has smartly capitalized on its place in country music history. Every September, thousands of music lovers crowd the streets of downtown Bristol for the Bristol Rhythm and Roots Reunion, a 20-stage festival whose headliners this year range from Wynonna Judd to St. Paul and the Broken Bones.

Next stop was Nashville, where I dropped in on the second-ever Americana Music Festival & Conference. I didn’t spend much time at the conference — I enjoyed hearing Rodney Crowell tell stories about the Nashville songwriter scene of the early 1970s, but I didn’t come to Nashville to be cooped up in a hotel meeting room. Instead, I spent hours looking through the 45s at Lawrence Record Shop on South Broadway, which had more singles than any record store I’d ever seen. The now-gone store was heaven for me, since I had a jukebox in my basement that hungered for new records to play.

AmericanaFest was just a small affair then. I saw the Drive-By Truckers at Springwater, of all places, with maybe 40 other people. They played a lot of songs from their newly released Southern Rock Opera album and blew me away.

Then it was off to Memphis, with a stop along the way at the Loretta Lynn Ranch. I hit Beale Street, of course, and Sun Studio, where I posed for a picture with the same microphone Elvis used. I was determined to go to a real juke joint, and I knew there weren’t many left in Mississippi, so I asked the Sun Studio tour guide if he knew of any in Memphis. He recommended Wild Bill’s, a small club far away from Beale Street’s tourist traps. I walked in and the place was packed. There was even a table of deaf people, who could feel the vibrations of the music through the floor. I ordered a Bud, and the bartender gave me a quart bottle and a glass. Until the next band showed up, I was the only white person there. I had found a real juke joint.

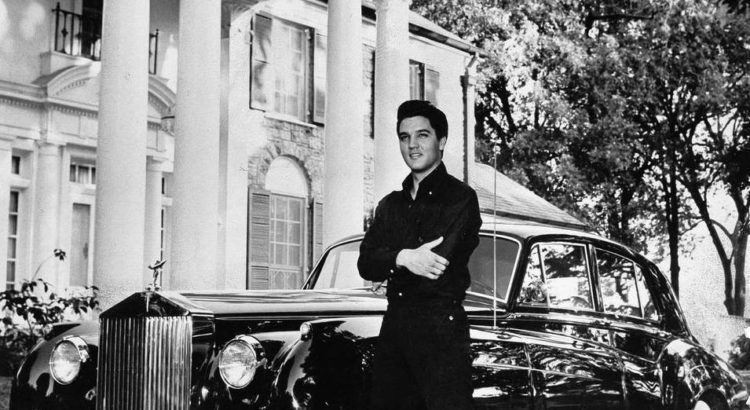

I stayed in a hotel downtown, across the street from Memphis’ minor-league baseball stadium. Big mistake — there was a late-night party at the stadium that night with hiphop music so loud that it rattled my hotel room’s windows. I couldn’t get to sleep. I complained to the hotel clerk the next morning, and she said, “Memphis doesn’t shut down at night.” It was Sunday, so I went to church — not just any church, but the Full Gospel Tabernacle Church, where the Rev. Al Green preached. I was surprised there weren’t more people there, but Al Green didn’t care. The soul singer turned preacher gave it his all, singing with the choir, preaching a little, singing some more, preaching some more, and so on. After two hours I wondered if the service was ever going to end, and I wanted to get to Graceland before it closed. Graceland turned out to be an island in the middle of a low-rent commercial district. It’s not that big of a mansion, and its stone wall was covered in graffiti. Inside, it’s a trip to see it furnished just like Elvis left it in 1977, and the homemade memorials that had been placed around his grave were touching. Plus Elvis’s cars and his airplane, the Lisa Marie, were fun to see.

I headed to Mississippi as the sun began to sink and landed in Batesville, where I was disappointed to find that I couldn’t buy a beer on Sunday. The next day I headed to Clarksdale, where I visited the Delta Blues Museum and ate lunch at the Ground Zero Blues Club, a sanitized version of a juke joint owned by actor Morgan Freeman and a local lawyer. Clarksdale already was on the map for blues travelers, but it was nothing like the blues mecca that it is today. Since it was a Monday, there was no prospect of seeing any live music that night. So I went rambling.

With Robert Johnson playing on my car’s tape deck, I drove through a bunch of crossroads until I got to Rosedale. Prisoners under the watchful eye of an armed deputy were working on the side of the road. I parked my car when I saw what looked like a juke joint. There was a guy sitting on a chair on the sidewalk by the door. I asked him if I could go in, and he said it was closed, but I could take a look. Inside the walls were covered with graffiti, and there was a DJ station, but no stage for a live band. Hiphop, not the blues, ruled.

I decided it was time to find Sonnyboy Williamson’s grave in Tutwiler. The most direct route, according to my map, was through Parchman. I didn’t realize until I got to a gate manned by armed guards that Parchman wasn’t a town, it was the notorious Parchman Farm, the prison where many bluesmen spent time. I could drive through it, they said, if I didn’t have a camera. I admitted to having a camera, so that’s one site I didn’t see.

I had to drive back to Clarksdale in order to get to Tutwiler, and it was pitch black by the time I got there. I couldn’t find Sonny Boy Williamson’s grave, but I did see where composer W.C. Handy first heard the blues in 1903 while waiting for a train.

I was tired from all this driving around, but I was ready to leave the Delta. So I drove all the way to Tupelo, where I planned to visit the home where Elvis was born. I stayed in a cheap motel and woke up with a fright in the middle of the night — I had dreamed there was a man at the motel room’s door looking in at me. Too much Robert Johnson, I guess.

Elvis’ birthplace was small and simple — a two-room house built by his father, grandfather and uncle. It didn’t take much time to see. I spent more time in a chapel on the museum’s grounds, where I sat alone on a wooden pew surrounded by stained glass, listening to gospel songs performed by Elvis. I found comfort in this peaceful setting, as I did later on this trip when I visited the Georgia Music Hall of Fame, where I listened to the music of Thomas Dorsey, the father of black gospel music, in a replica of a church sanctuary.

The rest of the trip was anticlimactic — I did make it to see Duane Allman’s grave in Macon, as well as the graves of Elizabeth Reed and Little Martha, the inspirations for two of the Allman Brothers’ songs.

I’ve gone down south many times since then, including numerous trips to Clarksdale, but most of my journeys are now taken on turntables and CD players. Thanks to WXNA, you can go with me.

I left the Washington, D.C., area in 2016 and moved to Kingston Springs and opened a record store. Turns out records are a better hobby than a business, at least for me, and I closed the store after one year. I did get to know several WXNA DJs through the store, however, and I jumped at the chance to join the WXNA team.

You can find all kinds of music and public affairs programming on WXNA, and I get the chance to play everything from Celtic music to New Orleans funk when I fill in for other DJs. But Southern roots music is still my first love, and that’s what you’ll hear on Goin’ Down South. Let’s ride!

Hound Dog Hoover

Goin’ Down South

Mondays, 1-3 p.m.